Second albums after a huge first hit are always tricky, but the famous econ duo of Jonathan Haskel and Stian Westlake pull it off with Restarting the Future: how to Fix the Intangible Economy, a sequel to their best-selling Capitalism Without Capital.

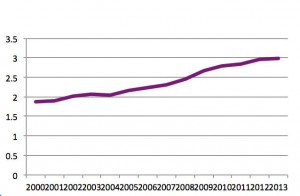

That title was missing a ‘Physical’ in parenthesis before ‘Capital’, because the point was to underline the relative importance of intangible capital in the economy now – everything from patentable drug formulae to reputation to social trust to the tacit know-how that makes complex organisations function. While intangibles have always been important in the economy, they now predominate in the creation of economic value. Indeed this has been the case for decades now (my book The Weightless World is 25 years old this year). Jonathan and Stian (who are friends of mine) set out the special characteristics of intangibles – fours Ss, scalability, sunkenness, spillovers, and synergies – and explored the implications.

The new book starts with the observation that all is not well in the economy, with a litany that has become all too familiar: stagnant productivity, excessive inequality, a lack of resilience, ‘dysfunctional’ competition and what they term inauthenticity. They note, too, that investment in intangibles has slowed down markedly. Their diagnosis is that while existing institutions (in the broad sense in which that term is used in economics) were able to support intangible growth up to a point, progress now will depend on institutional reform: “institutions are out of sync with the intangible economy”. In their sights for reform are institutions and policies to support better (and fund) research and development, a redesigned competition policy, improvements to the financial architecture and monetary policy, and fixing cities.

The first half of the book is diagnosis, including rejecting some alternative diagnoses. In particular, they reject the idea that markets have become too concentrated, arguing that firms’ mark-ups have not risen when their intangibles are measured properly. I must say I don’t find this persuasive, given for example the steady consolidation of service sectors (pharmacies, vets, private healthcare, accountancy firms, financial advisers….) or simply observing the steady degrading of big tech service offers (eg Amazon searches being dominated by paid-for items). Still, competition policy certainly needs (and is getting) a refresh. Nor does this mean the intangibles explanation is invalid – on the contrary, it seems to be an integral part of the way production has been restructured.

The second half of the book then goes on to recommendations for reforms of policies and institutions, all rather sensible albeit not tangling with the politics of how these changes might come about except to observe that winners from the old regime will use their power to lobby against change.

I have some other quibbles. Jonathan and Stian put James Scott (Seeing Like A State) and Ernst Schumacher (Small is Beautiful) in the same ideas basket, which seems a bit odd to me although it’s decades since I read Schumacher. I don’t really understand their argument about inauthenticity, which draws on Graeber’s ‘bullshit jobs‘ and on Baudrillard, as an economic phenomenon – I decided it was about (lack of) trust or social capital but am not sure. The chapter on competition seems to claim that the debate about big tech etc only has one proposition, namely break-up, whereas in fact there is a rich debate about reshaping competition policy and enforcement in these large scale, spillover-laden markets. It also shoehorns in positional arms races in the jobs market into the ‘dysfunctional competition’ basket, when this is ja distinct labour market phenomenon.

But these really are quibbles about an excellent book. Their fundamental point about institutions lagging the structure of the economy is spot on, as is the implication that different kinds of collective approaches are needed to the economy. In the world of the four Ss, individualism and market-knows-best policies make for stagnation and discord. A final note: the book is published as the Russian invasion of Ukraine reminds us that tangibles from tanks to wheat really matter too. Simon Schama writes in the Financial Times that Ukraine’s ‘software’ has so far held out better than anybody might have feared against Russia’s hardware. But the world of the post-1989 era is changing.