I’ve long enjoyed the blog posts by Richard Jones on economic productivity and growth – his perspective from physics is always interesting. As I met him in real life for the first time this past week, I also downloaded his free e-book Against Transhumanism (download here) – a brief, compelling demolition of the idea that digital technology is hurtling us towards a ‘singularity’. The most famous transhumanist is Ray Kurzweil, I suppose, of [amazon_link id=”0715635611″ target=”_blank” ]The Singularity is Near[/amazon_link]. Prof Jones points out that:

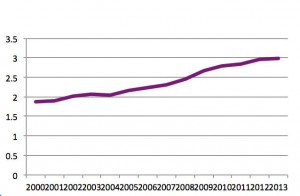

a) exponential growth (as per Moore’s Law) cannot deliver a singularity, as the value of expnential functions is finite – unless the rate of technological improvement is constantly increasing without limit. Seems a stretch, looking at either current productivity figures or any history at all.

b) transhumanism is an apocalyptic religion, not a scientific theory.

c) To quote the e-book: “The idea that history is destiny has proved to be an extremely

bad one, and I don’t think the idea that technology is destiny will necessarily work out that well either. I do believe in progress, in the sense that I think it’s clear that the material conditions are much better now for a majority of people than they were two hundred years ago. But I don’t think the continuation of this trend is inevitable. I don’t think the progress we’ve achieved is irreversible, either, given the problems, like climate change and resource shortages, that we have been storing up for ourselves in the future. I think people who believe that further technological progress is inevitable actually make it less likely – why do

the hard work to make the world a better place, if you think that these bigger impersonal forces make your efforts futile?”

It’s well worth a read, along with the Soft Machines blog.There is a super-clear explanation of the implications of nano-technology,as you might expect from the author of the [amazon_link id=”0199226628″ target=”_blank” ]Soft Machines [/amazon_link]book.

[amazon_image id=”0198528558″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]Soft Machines: Nanotechnology and Life[/amazon_image]

There’s also a chapter on why it’s unlikely you’ll ever be able to upload your brain to the cloud. Above all, though, the book explains why transhumanism is a Dangerous Idea. The idea of a Singularity has been described as the ‘Rapture of the Nerds’ (attributed to [amazon_link id=”1857238338″ target=”_blank” ]Ken McLeod[/amazon_link]), which makes it sound like the lunatic fringe. But as Prof Jones points out, the Silicon Valley crowd are seriously influential; and their view that technology has its own irresistible dynamic – the techno-determinism – elbows aside the truth that the results of technological discovery are socially determined: “Why would you want to think of technology, not as something that is shaped by human choices, but as an autonomous force with a logic and direction of its own? Although people who think this way may like to think of themselves as progressive and futuristic, it’s actually a rather conservative position, which finds it easy to assume that the way things will be in the future is inevitable and always for the best.”

Written by a physicist but like a true social scientist. The future is multiple, not singular.