A new paper by Professor Nicholas Crafts of Warwick University dropped into my inbox today, Saving the Eurozone: Is A Real Marshall Plan The Answer? This means ‘real’ as in ‘structural’ or ‘supporting the real economy’, which economic historian Prof Crafts points out was the purpose of the original Marshall Plan. He writes:

“Faster productivity growth in the euro periphery could help improve competitiveness, fiscal arithmetic and living standards; the main role of a real Marshall Plan would be to promote supply-side reforms that raise productivity growth. This would repeat the main achievement of the original Marshall Plan of 1948.”

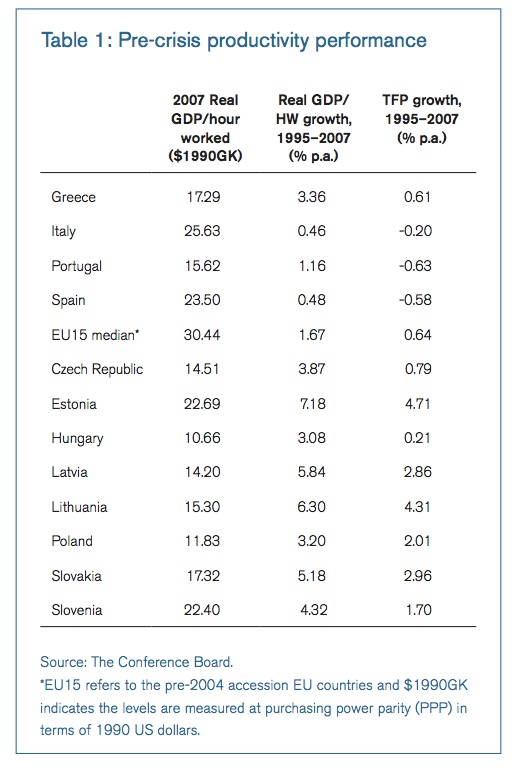

In advocating this course of action, he points out that a plan of this kind, investing in infrastructure for example, would not alleviate the need for fiscal federalism and effective European-level democracy – these steps being the lesson of the 1930s experience. But it would support those moves by encouraging faster growth in the southern periphery. One of the most striking tables in the report contrasts the dismal productivity performance of Greece, Italy, Spain and Portugal from 1995-2007 with the much faster productivity growth of 2004 accession countries such as Lithuania, Estonia and Poland.

Productivity in the Eurozone

The paper is pretty sobering – what analysis of the Eurozone isn’t? I think the Marshall Plan analogy is an interesting one. In a nice OECD book I have, [amazon_link id=”9264155031″ target=”_blank” ]From War to Wealth[/amazon_link], published for the 50th anniversary of its founding as the Organisation for European Economic Cooperation, Marshall’s speech is quoted:

“The remedy seems to lie in breaking the vicious circle and restoring the confidence of the people of Europe in the economic future of their own countries and of Europe as a whole.”

He strongly emphasised the need for co-operation – hence the OEEC.

Professor Crafts’ Real Marshall Plan would link Structural and Cohesion funds conditionally to specific structural reforms. He suggests this might achieve a 1% point a year increase in productivity growth. The paper concludes:

“The experience of the Gold Standard’s collapse in the 1930s suggests that seeking to keep the eurozone intact by imposing a ‘golden straitjacket’ on the policy choices of independent nation-states is not a viable option. This points to fiscal federalism with genuine democracy at the EU level as the long-run solution; a new Marshall Plan may not be a substitute for reforms of this kind, but it can certainly serve as a valuable complement.”

[amazon_image id=”9264155031″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]From War to Wealth: 50 Years of Innovation[/amazon_image]