In 2005 the UK Treasury sponsored a conference with the title [amazon_link id=”023001903X” target=”_blank” ]’Is There a New Consensus in Macroeconomics?[/amazon_link]’; a book of the conference was published in 2007. Its answer was ‘yes, but….’, the ‘but’ being – correctly, as it turned out in hindsight – the flagging up of some puzzles and controversies as well as shortcomings such as the absence of international flows and imbalances in the conventional model. At the time this sense of consensus was (by definition) widespread – Olivier Blanchard at the IMF famously wrote about it too, in The State of Macro.

[amazon_image id=”023001903X” link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]Is there a New Consensus in Macroeconomics?[/amazon_image]

Earlier this week, the ESRC sponsored a symposium on macroeconomics hosted by the Oxford Martin School, with the aim of evaluating the state of macro now. As the ESRC’s Adrian Alsop put it in his introduction: “While in the economics profession, macro is but a sub-set of what we do, any perceived lack of vitality and strength in macro tarnishes economics as whole in the eyes of citizens and policy makers alike; and that in turn causes reputational damage for the whole of social science. So this is big stuff the profession, let alone the funding agencies.” Internationally, funding agencies are considering what kind of research in macro is needed – and particularly in the UK, where this is an area of economics in this country flagged up as weak by a 2008 benchmarking study (scroll down) for the ESRC, led by Elhanan Helpman.

My headline from the symposium is that macroeconomists are deeply divided, with any sense of consensus shattered. There is a division between those who regard increasing the sophistication and flexibility of existing models and approaches as an adequate response to the crisis, and those who believe a more far-reaching re-tooling is essential for both scientific and public policy credibility. This is more or less the same as the division between adherents to DSGE models, or more broadly a deductive equilibrium framework that uses a small number of aggregate variables to make analytical predictions; and those who believe macroeconomics must now become more inductive and data-based. As Professor Neil Ferguson, Professor of Mathematical Biology at Imperial College, put it in his comment on day 2 of the symposium, he was astounded by how little macroeconomists discussed data and the new techniques available for handling large amounts of data.

When this division between deductive and inductive approaches, between parsimonious analytical models and computer-based statistical techniques (agent-based modelling, econo-physics, statistical exploration of the data) surfaced, the discussion grew a little heated. This included the breaks: many of those who disagree with the prevailing, albeit broken, ex-consensus feel unable to bring about change even in their own research, and are not eager to speak out or change the nature of their work because it will harm their career prospects. To advance in UK economics departments requires publication of numerous articles in a small number of American journals which are firmly sticking to the conventional modelling approach.

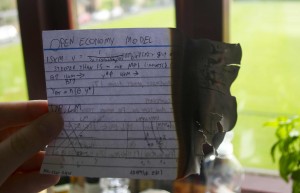

My view is that if macroeconomics does not abandon its obsession with being able to write down analytical 3 equation models with maybe 12 or even 20 variables to explain and predict what is happening at large scale in the economy, it will lose all meaning and purpose. Below is a picture of my son burning his macroeconomics notes as soon as he’d taken his final exam – despite having an outstanding teacher, it seemed obvious to him that macroeconomics was a fairy tale, a fable. Yet many macroeconomists seem not to realise that they are dealing in metaphors, and that IS-LM curves are more like unicorns than Higgs bosons. Microeconomics suffers in the same way but not so badly and applied microeconomists are already a bit more flexible – more willing to use ad hoc rules of thumb derived from behavioural psychology, more willing to use qualitative evidence and business data, not just highly aggregated time series data.

Burning unicorns?

So I was wholly in agreement with Professor David Hendry, who in his presentation on statistical techniques for exploring data, said:

– all macroeconomic theories are incomplete, incorrect and changable

– all macroeconomic time series are aggregated, inaccurate and rrely match theoretical concepts

– all empirical macroeconometric models are aggregated, inaccurate and mis-specified in numerous ways

So why justify an empirical model by an invalid theory that will soon be altered? Why is internal model credibility considered more important than verisimilitude? “It’s why people think economists are daft,” he said. And, as he pointed out, DSGE models are not even logically internally consistent because they incorrectly regard agents’ expectations today of the future state of the world, conditioned on what they know today, as the same as their equivalent expectations tomorrow, bar for an unpredictable error – but this would only be true in a stationary world. When the state of the world can change in a non-stationary way between today and tomorrow, the kind of ‘model-consistent’ or rational expectations conventionally used are not possible.

I hope the ESRC and other social science funders will focus their efforts on enabling the reformist macroeconomists to pursue their alternative approaches. None of us knows what approach to macroeconomics will ultimately prove most fruitful, but at present given the institutional structures in academia, none of the alternatives are being pursued. Academic economists who have spent their careers doing everyday macroeconomics will need 2 or 3 years to change direction and learn new techniques and approaches to data. But if they want to keep their jobs, they will not get the space to do that – they will need to publish another tweak on a DSGE model in the American Economic Review.

Following the conference earlier this year that resulted in [amazon_link id=”1907994041″ target=”_blank” ]What’s The Use of Economics[/amazon_link], a working group hosted by the Government Economic Service has been considering the institutional barriers to reform of the undergraduate curriculum, and we will report next year. A parallel consideration is needed of barriers to reform in research, and I don’t excuse microeconomists from the need to think deeply about their subject, but it’s more urgent in macroeconomics because of the crisis.