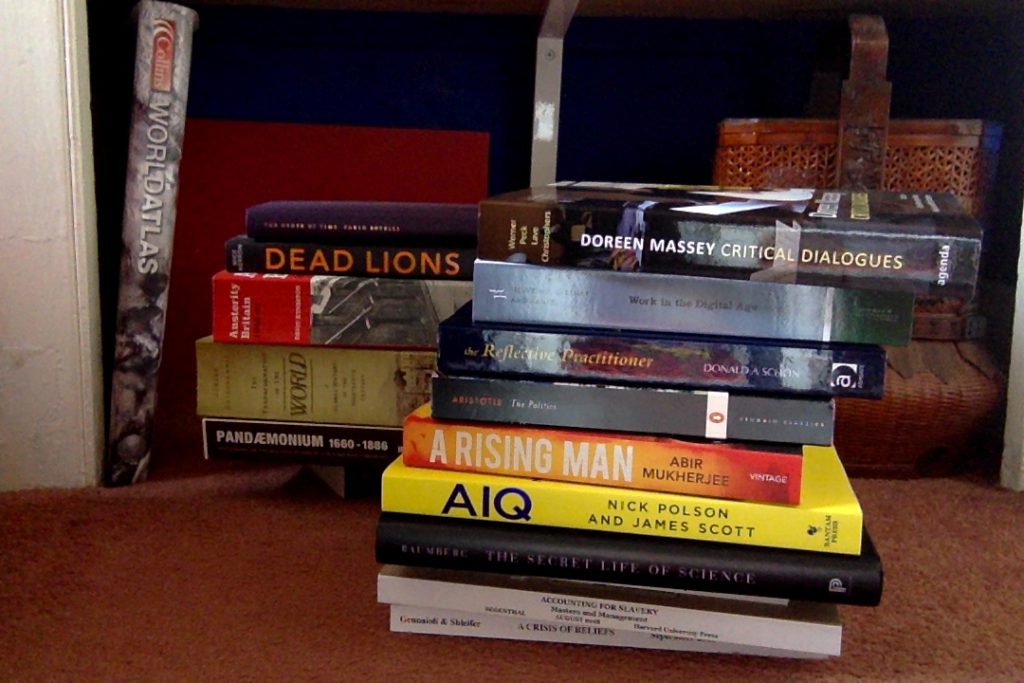

The Secret Life of Science: How it Really Works and Why It Matters by Jeremy Baumberg won’t hold many surprises for economists working in academia. The increasing role of publication metrics in career prospects, even though everyone knows them to be counter-productive or even pernicious. The narrowing of scholarly horizons within disciplinary silos partly for this reason and partly (in the UK) because of the REF exercise. The creaking peer review system. The debate about open access and the monopoly power of certain journal publishers. I don’t know whether the same is true in the humanities and other social sciences, but the description of the systemic pressures and the way they make it ever harder to allow intellectual curiosity and boundary-crossing work free rein – for some very good reasons – makes this book a reflection on more than the natural sciences, but rather on the institutional framework for research as a whole, into which citizens pour a good deal of funding.

There are, however, additional issues in the sciences, not least the very high cost of equipment and facilities in some areas, and the failure of the funding system as a whole to be able to reflect on and implement societal priorities. Another difference is the institutional framework, with much scientific research (to varying degrees across countries – there are interesting figures in the book) occurring in the private sector. Baumberg also discusses the ever-rising number of scientific researchers, in what seems to be a sort of winner-takes-all dynamic of funding concentrating in elite groups and no signs of increasing diversity, producing seemingly ever-decreasing returns.

Although the issues may be familiar, the book usefully presents them all as a combined system challenge. It is pretty factual and even handed, but one ends with a strong sense of the need for some system-wide reforms. Baumberg has no silver bullet solution, and quite right too. He makes some suggestions such as introducing other kinds of metrics than citations, finding some ‘anarchic’ ways to fund science, creating better and different career structures for postdocs.

I read the book just after Richard Jones’s and James Wilsdon’s thought-provoking and trenchant report on ‘biomedical bubble’ in the UK. I doubt The Secret Life of Science will appeal to the general audience as it’s much more about the institutional framework than about the scientific research. But although researchers will already know – and live in their daily lives – the issues flagged up in the book, it’s a timely warning that the scientific endeavour that has brought our societies astonishingly greater prosperity and improvements in the quality of life is sclerotic and failing to deliver for the societies funding research. Hard as it may be for a young researcher struggling under all these pressures to regard herself as part of the despised ‘elite’, that’s the big issue facing scientific and other research. Time to tackle it.

[amazon_link asins=’0691174350′ template=’ProductAd’ store=’enlighteconom-21′ marketplace=’UK’ link_id=’d3269161-8fdb-11e8-8b3d-e1165f417ac3′]