Last night I started reading [amazon_link id=”0099552450″ target=”_blank” ]This is not the end of the book[/amazon_link], by Umberto Eco and Jean-Claude Carrière – a very Euro-intellectual offering (a ‘curated conversation’) sponsored by the French Ministry of Culture. I’m loving it, as one of those Anglo-Saxons who wishes we were allowed to have intellectuals here in the UK. One of Eco’s early points is that it doesn’t do to get worked up about formats:

“The book is like the spoon, scissors, the hammer, the wheel. Once invented, it cannot be improved. You cannot make a spoon that is better than a spoon.” (p4)

And he goes on to point out that no formats last. Papyri have crumbled. Books printed on wood pulp that are 50 years old are crumbling too. Computer discs are obsolete. Online is insecure – as the saga of 3am magazine’s recent disappearance dramatically reveals. (Its rescue came about thanks to the magazine’s Twitter followers tracking down the former owner of the server to a Missouri tattoo parlour.)

[amazon_image id=”0099552450″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]This is Not the End of the Book: A conversation curated by Jean-Philippe de Tonnac[/amazon_image]

Serendipitously, this morning’s FT reports Bloomsbury’s latest results, which reveal a 70% year on year increase in e-book sales in the first quarter, offsetting a 2% decline in revenues from physical books. But CEO Nigel Newton dismissed the idea that e-books are killing real books:

“It will be a mixed market. Just as it has been for 40 years for hardback and paperback formats – it’s just another new format.”

Eco and Carrière in fact conclude that in the age of the computer, words have become more important than ever. We are communicating more than ever, and in words not pictures. In books, e-pamphlets, blogs, public lectures and debates, tweets… As we seem to need to rediscover every time a new communication technology happens along, modes of communication are complements, not substitutes.

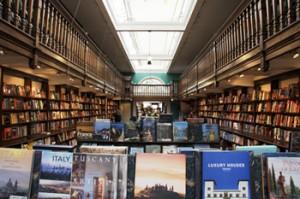

As a footnote, the FT has also been running a very good series on Amazon all week. In another happy coincidence, today’s feature is about its mixed success with digital formats – a strong performance in e-books, not so great in music and video. This is consistent with my view that publishing and bookselling have been relatively successful in innovating with the new technologies, in contrast to the music industry.