I spent a chunk of the weekend reading some of the classics of national accounting – or ‘social accounting’ as one of the pioneers, Richard Stone, preferred to call it.

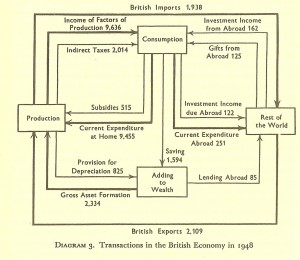

It was amazing to find a section of his 1948 Newmarch Lectures, [amazon_link id=”0751201863″ target=”_blank” ]The Role of Measurement in Economics[/amazon_link], explaining that the accountancy presentation of the national economy we are so familiar with can equivalently be presented as a network structure: “The different forms of economic activity are nodes and the transactions are represented by directed branches passing from one node to another. The only formal property of such a system is that the sum of the flows at any node is equal to zero.”

A handful of economists such as Paul Ormerod (including in his new book [amazon_link id=”0571279201″ target=”_blank” ]Positive Linking [/amazon_link]- reviewed here by Anthony Painter at the weekend) and Alan Kirman have long been interested in network models of the aggregate economy. And the general degree of interest is on the increase, thanks in no small part to the interconnectedness paraded by the world’s banks during the past few years.

Reading Stone made me wonder how differently our thinking about the aggregate economy would have turned out if we had not gone down the path of the accounts presentation. That suited the econometric models being developed contemporaneously by Jan Tinbergen, also described in these lectures. Without quite saying so, Stone expresses some scepticism about the then-new macroeconometric models, cautioning about identification problems, structural change, standard errors, non-stationarity – in short, the illusory nature of the seemingly precise numerical projections they permitted. A network habit of thought instead would surely have focused macroeconomists on interconnectedness rather than consumption functions.

[amazon_image id=”0571279201″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]Positive Linking: How Networks Can Revolutionise the World[/amazon_image]