On my journeys to and from The Hague this week (one of the joys of travel – offline time when nobody can email, phone me or ask me what’s for dinner), I read Jonathan Schlefer’s enjoyable [amazon_link id=”0674052269″ target=”_blank” ]The Assumptions Economists Make[/amazon_link]. It’s a book of two halves: a combination of a critique of modern economic methodology in general and a polemic against actually existing neoclassical economics in particular. The former, the first half, is much stronger, although the latter is probably more populist. The two halves will also appeal to different audiences – to professional economists and other social scientists in the first case, and to more general readers who are inclined to blame economics for the mess we’re in in the second.

The author is a political scientist and writer who undertook the commendable task of learning economics and reading widely before embarking on a critique. This distinguishes him from almost all other non-economist critics and in itself means economists must offer him equal respect and take this book seriously. The book starts with a very clear description of general equilibrium theory and the microfoundations built on it. Schlefer makes some extremely interesting points about the theory, drawing on the literature – as he notes, there is a “breach between the subtle world of proper neoclassical theory, which faces quandaries head on, and the corrupt world of neoclassical practice, which just ignores those quandaries.” (p89) One point, for example, is why a stable equilibrium cannot exist in the imaginary general equilibrium economy. All students of economics learn about the impossibility theorem – and then motor on with the rest of their studies as if it were not true. Similar points have been made elsewhere, such as Steve Keen’s [amazon_link id=”1848139926″ target=”_blank” ]Debunking Economics[/amazon_link], but I found it to be much clearer in [amazon_link id=”0674052269″ target=”_blank” ]The Assumptions Economists Make[/amazon_link].

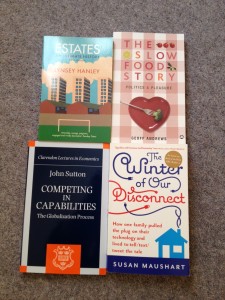

The first chapters set out the basics of economic theory through a history of thought progression from Adam Smith to the marginalists – Jevons stands out here – along with Walras and Menger – as the driving force in turning economics into a purely deductive science concerned with (in his words) ‘the mechanics of self-interest and utility’. (p76) (I wanted to know more about Jevons, especially having seeing his Logic Machine (below) in a Science Museum exhibition.)

Jevons’ Logic Machine (‘The machine is capable of replacing for the most part the action of thought required in the performance of logical deduction’.)

The book then turns to the consequent flaws in basic microeconomics, especially the concept of the production function and the assumption of marginalism and competition in investment. It revisits the ‘Two Cambridges’ debate (which I was taught about in graduate school, but with the neoclassical side the unquestioned victor in the version I learned), and goes on to question the logical coherence of aggregation in the way it’s done in conventional macroeconomics. Well, I’m with that idea wholeheartedly; my own journey from macroeconomics to micro started with a PhD thesis that confronted macro labour market models with industry-level data, a very effective way of lifting the rock of aggregation to reveal the nasty creepy-crawlies underneath.

However, after that, the book becomes less compelling for me. Schlefer spends the remaining chapters discussion Keynesianism as the master intended it and as his neoclassical interpreters shaped it in the post-war years. This is well-written, and I enjoyed discovering, for example, that Paul Samuelson was almost regarded as a dangerous Commie for taking Keynes seriously, so paranoid was early Cold War America (p192). However, a turn to a discussion of macroeconomic aggregates not what I wanted to read as a follow-on to a persuasive argument about why macroeconomic aggregates are problematic. Schlefer, like Keen in his book, attacks the conventional three-equation DSGE models – quite right too – but seems to want to replace it with an alternative abstract macro framework. Keen’s is a Minsky-esque version of disequilbrium dynamics. Schlefer’s is a structuralist approach following his teachers, especially Lance Taylor. (No doubt he would approve of Justin Yifu Lin’s [amazon_link id=”0691155895″ target=”_blank” ]The Quest for Prosperity[/amazon_link], setting out a ‘new structural economics’, although he doesn’t cite it.) He also mentions favourably ecological models.

He writes: “It is legitimate to impose informed assumptions on macro data – profits, wages, consumption, investment and the rest – in order to build rough macroeconomic models of cause and effect. The role of models is to be sure that assumptions are consistent, to understand their implications as well as possible, and to frame a coherent view that you can compare with historical experience.” (p267) The huge mistake in modern macro, he says, was introducing the illusory quest for ‘microfoundations’. I suppose it’s correct to say an assumed macro framework is necessary, but this leaves me with a question not answered here, which is how on earth we should choose between them. Schlefer obviously likes the look of ecological predator-prey models. Other critics of macroeconomics prefer agent-based modelling, or econo-physics-style empirical exploration of datasets to derive regularities. Steve Keen has his own Keynes-Minsky set of abstractions. Many mainstream macroeconomists are insistent on the relevance of New-Keynesian DSGE models with stickiness in wages and prices, and some finance added in, post-crisis. [amazon_link id=”0674052269″ target=”_blank” ]The Assumptions Economists Make[/amazon_link] raises important questions but doesn’t answer the one raised half way through the book: “Is macroeconomics possible? There are serious doubts.”

[amazon_image id=”0674052269″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]Assumptions Economists Make[/amazon_image]