I’ve got some way into Bernard Carlson’s book [amazon_link id=”0691165610″ target=”_blank” ]Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age, [/amazon_link]which is out in paperback now. It’s very interesting, although the physics washes over me. The difference between a rotor, a stator, a transformer and a conductor? It just doesn’t stick. It must be like this for non-economists reading about economics. Anyway, the terms make sense once if you concentrate really hard but then just evaporate from the mind.

[amazon_image id=”0691165610″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age[/amazon_image]

On the other hand, I’m finding the depiction of the early electrical industry in the US and Europe very interesting – the fierce competition, patenting of different approaches, seriously risky capital investment, the uncertainty over what would emerge as an industry standard, the dastardliness of some rich investors, the works.

One chapter describes Tesla’s early investors and how they got interested in electricity. One had started with a telegraph line between Washington DC and Chicago: “Peck discovered that there were banks and merchants who were interested in leasing dedicated wires in order to conduct their business securely.” So, as now, the finance industry was a big customer of the new technologies.

I also liked this parallel with modern times: Tesla persuaded his investors to provide more funds with a demo involving spinning an egg on its pointy end on a wooden table thanks to some electrical whatevs underneath. They loved it. “This episode taught Tesla that invention would require a degree of showmanship in order to create the right illusions about his creations. People do not invest in inventions built out of tin cans; they invest in projects that capture their imagination.”

And, to my delight in these early chapters, Tesla turns out to have got his start at the Ganz electrical works in Budapest. I visited the factory in early 1990, when it took immediate advantage of the collapse of communism to look for western investors, and hired a stockbroker from London who took some journalists (including me) on a trip. It was fascinating. The managing director’s secretary had the only key to the cupboard in which the toilet paper was kept so she knew exactly when everybody in the party had to go – clearly a powerful woman in the enterprise. The factory itself was ginormous and took in steel, ore and coal at one end and turned out trams and ligh bulbs at the other end. Spectacular. Monstroously inefficient.

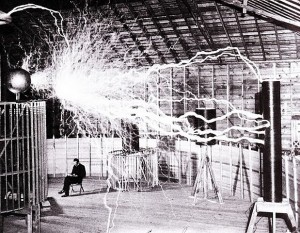

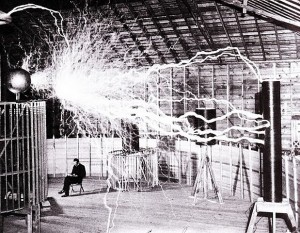

I’m 4 chapters in. Have always loved this image of Tesla.

Nikola Tesla