One of the best books about the effect of digital technology on business dates from 1999. [amazon_link id=”087584863X” target=”_blank” ]It’s Information Rules: A Strategic Guide to the Network Economy[/amazon_link] by Carl Shapiro and Hal Varian (now chief economist at Google). Until recently, I’ve thought it didn’t need updating, for although the examples are obviously dated, the principles are not.

[amazon_image id=”087584863X” link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]Information Rules: A Strategic Guide to the Network Economy[/amazon_image]

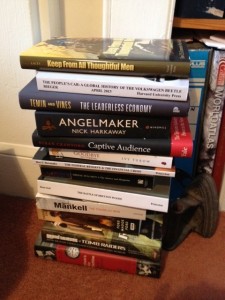

However, a couple of excellent recent books on the telecommunications and media sector have made me start to wish for an update of Information Rules. They are Timothy Wu’s [amazon_link id=”1848879865″ target=”_blank” ]The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires[/amazon_link] and Susan Crawford’s new book, [amazon_link id=”0300153139″ target=”_blank” ]Captive Audience: The Telecom Industry and Monopoly Power in the New Gilded Age.[/amazon_link] Telecoms is obviously a network industry, with the characteristic kind of increasing returns to scale you get with networks.

[amazon_image id=”1848879865″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires[/amazon_image]

[amazon_image id=”0300153139″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]Captive Audience: The Telecom Industry and Monopoly Power in the New Gilded Age[/amazon_image]

Both these newer books are excellent on the sector. What I’d like is an update – beyond the one chapter in the 1999 edition of Shapiro and Varian – on business strategy and market dynamics (including two-sided aspects) in network markets. For digital connectivity is making the network aspect more prominent in other sectors. Finance is obviously one, but there are more sectors where digital technologies are enabling new forms of intermediation as well as disintermediating old forms, where there are information asymmetries or experience goods, and where access to new platforms is becoming vital. Consider publishing, or indeed even retailing – say a new fashion designer facing a declining physical high street.

So here’s a modest proposal: please will somebody write about these new market dynamics (and the competition and distributional implications) where we need two-sided market models, increasing returns and non-linearities, and the experience good/public good characteristics taken into account?!