It has seemed a good moment to reflect on the European big picture. As mentioned in a previous post, Tony Judt’s [amazon_link id=”009954203X” target=”_blank” ]Postwar A History of Europe Since 1945[/amazon_link] is a marvellous long-run history of the whole European continent. Its inclusion of the central and eastern European countries in the story gives the British reader a subtle but useful shift of perspective, far wider than our usual local take on our relationship with the rest of Europe. This morning I picked up a 1996 book, [amazon_link id=”052149964X” target=”_blank” ]Economic Growth in Europe since 1945[/amazon_link], edited by Nick Crafts and Gianni Toniolo. The overview chapter similarly offers an interesting perspective, rather different from the one that’s at front of mind as we ponder the slow but still seemingly almost inevitable disintegration of the Euro.

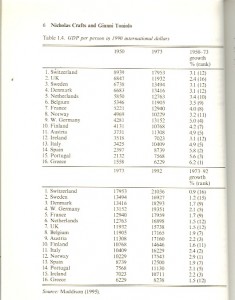

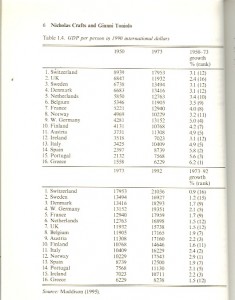

Take for example the following table, which uses Angus Maddison’s indispensable long-run GDP data.

One of the standouts is Greece, fastest growing from 1950-73, then one of the slowest from 1973-92, whereas Spain, Portugal and Italy all remained in the top ranks for growth. The UK’s growth ranking has been lacklustre for more than two generations – slowest growing of all 16 countries listed in the first period, not much better in the second. France and Germany have seen solid growth throughout – although of course the average is much lower for the second period than for the previous ‘golden age’ of growth.

One of the standouts is Greece, fastest growing from 1950-73, then one of the slowest from 1973-92, whereas Spain, Portugal and Italy all remained in the top ranks for growth. The UK’s growth ranking has been lacklustre for more than two generations – slowest growing of all 16 countries listed in the first period, not much better in the second. France and Germany have seen solid growth throughout – although of course the average is much lower for the second period than for the previous ‘golden age’ of growth.

The authors (writing, remember, in the mid-90s) discuss the possible explanations for these patterns. They conclude that there is little evidence for export-led growth theories. Investment, capital stocks, and education, determining productivity and supply capacity, are most important in the long run trends. This is interesting in the context of a crisis that is clearly shaped in large part by the inability of the peripheral countries in the Eurozone to devalue. Perhaps the right conclusion is that the devaluation option is important for financial and fiscal reasons rather than for long-term growth potential – but I’d be interested in others’ thoughts about that. One of the challenges facing macroeconomics at present is how short-terms add up to the long-term….

Either way, Greece looks in terrible shape. I’m mid-way through the Greece chapter of Michael Lewis’s brilliant book, [amazon_link id=”1846144841″ target=”_blank” ]Boomerang: the Meltdown Tour[/amazon_link], which makes it abundantly clear that Greece should never have been allowed into the Euro in the first place. Given that the new head of the Greek statistical agency is being taken to court over his lack of patriotism in publishing less inaccurate figures on the Greek economy, there is obviously quite a way to go before the debate there turns to these longer term issues.

[amazon_image id=”052149964X” link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]Economic Growth in Europe since 1945[/amazon_image]

One of the standouts is Greece, fastest growing from 1950-73, then one of the slowest from 1973-92, whereas Spain, Portugal and Italy all remained in the top ranks for growth. The UK’s growth ranking has been lacklustre for more than two generations – slowest growing of all 16 countries listed in the first period, not much better in the second. France and Germany have seen solid growth throughout – although of course the average is much lower for the second period than for the previous ‘golden age’ of growth.

One of the standouts is Greece, fastest growing from 1950-73, then one of the slowest from 1973-92, whereas Spain, Portugal and Italy all remained in the top ranks for growth. The UK’s growth ranking has been lacklustre for more than two generations – slowest growing of all 16 countries listed in the first period, not much better in the second. France and Germany have seen solid growth throughout – although of course the average is much lower for the second period than for the previous ‘golden age’ of growth.