Joe Queenan has written an essay in the Wall Street Journal (based on his new book, [amazon_link id=”0670025828″ target=”_blank” ]One For The Books[/amazon_link]) about how he became addicted to books.

[amazon_image id=”0670025828″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]One for the Books[/amazon_image]

Books, books, books. I love them too. I always read books about books: Susan Hill’s [amazon_link id=”1846682665″ target=”_blank” ]Howard’s End is On The Landing[/amazon_link]; Francis Spufford’s [amazon_link id=”0571214673″ target=”_blank” ]The Child That Books Built[/amazon_link]; Ann Fadiman’s[amazon_link id=”0140283706″ target=”_blank” ] Ex Libris[/amazon_link], and so on.

The best bit of Queenan’s very funny essay is his defence of the need for books, the physical objects. He writes:

“Books as physical objects matter to me, because they evoke the past. A Métro ticket falls out of a book I bought 40 years ago, and I am transported back to the Rue Saint-Jacques on Sept. 12, 1972, where I am waiting for someone named Annie LeCombe. A telephone message from a friend who died too young falls out of a book, and I find myself back in the Chateau Marmont on a balmy September day in 1995. ….

None of this will work with a Kindle. People who need to possess the physical copy of a book, not merely an electronic version, believe that the objects themselves are sacred. Some people may find this attitude baffling, arguing that books are merely objects that take up space. This is true, but so are Prague and your kids and the Sistine Chapel. Think it through, bozos. …. There is no e-reader or Kindle in my future.”

I read this inwardly shouting, ‘Yes! Yes!” I too use travel tickets as bookmarks and leave them in the book, the better to remember reading them the cafe in Verona or on the flight to Belfast.

Flying back from Belfast

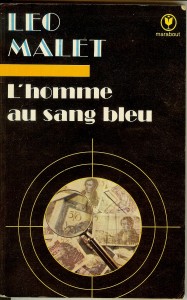

The part Queenan misses out it the joy of second hand books and bookshops. On my flight back from Belfast I finished reading a beaten-up old Leo Malet story about his detective Nestor Burma, [amazon_link id=”B003BPT2L4″ target=”_blank” ]L’homme au sang bleu[/amazon_link].

L’homme au sang bleu

I bought it on our summer holiday in Brittany in this marvellous warren-like bookstore, open only in the afternoons, seducing tourists as they drive past towards Cap Frehel.

Bouquinerie

I have many objections to e-readers, but perhaps the biggest is that they prevent the sharing of books. I can’t read the same books as my husband, who has a dreadful e-book habit, so I can’t talk to him about them. I couldn’t put e-thrillers I’ve read on the book-swap shelf at the local station. I wouldn’t be able to take them to the charity shop or sell them to a second hand bookstore. But what kind of civilisation would we be without second hand bookstores?