What’s the connection between ape selfies, the relationship between art and money, and e-book prices?

There have been interesting posts about each of these subjects this week, making the connection clear.

That ape selfie – Wikipedia has rejected photographer David Slater’s claim to own copyright in the picture, arguing that the animal took the photo. David Allen Green wrote a fascinating FT blog about UK law on this question. The law here says the ape can’t hold copyright but it doesn’t necessarily belong to the camera owner – it depends on the circumstances. Green concludes:

“A thing made by an animal may well be appreciated by humans, but not everything liked by humans can be bought and sold as a chattel or as an intellectual property right. And so when such things do occur, we should not seek to monetise them as some form of property; we should instead realise how lucky we are that such wonderful things exist at all.”

Mr Slater’s view is that as a professional photographer, he needs to be able to monetise pictures captured by his camera. Which takes us to a long n+1 essay on payment for art. It used to be that artists (including writers) who made money were “sellouts”, but now the complaint is that it’s becoming impossible to make money from art because of the ease of digital copying. Hence all the intellectual property debates, and the madness of copyright lasting for 70 years after the death of an author, as if length of term somehow compensates for loss of enforceability. As the essay concludes: “One did not become a writer in order to starve, but nor did one become a writer in order to get rich.” (George Gissing certainly didn’t.) And besides – as the incomparable Dave Birch pointed out to me with this link – there are ways of making money, even if not the same ways as of yore.

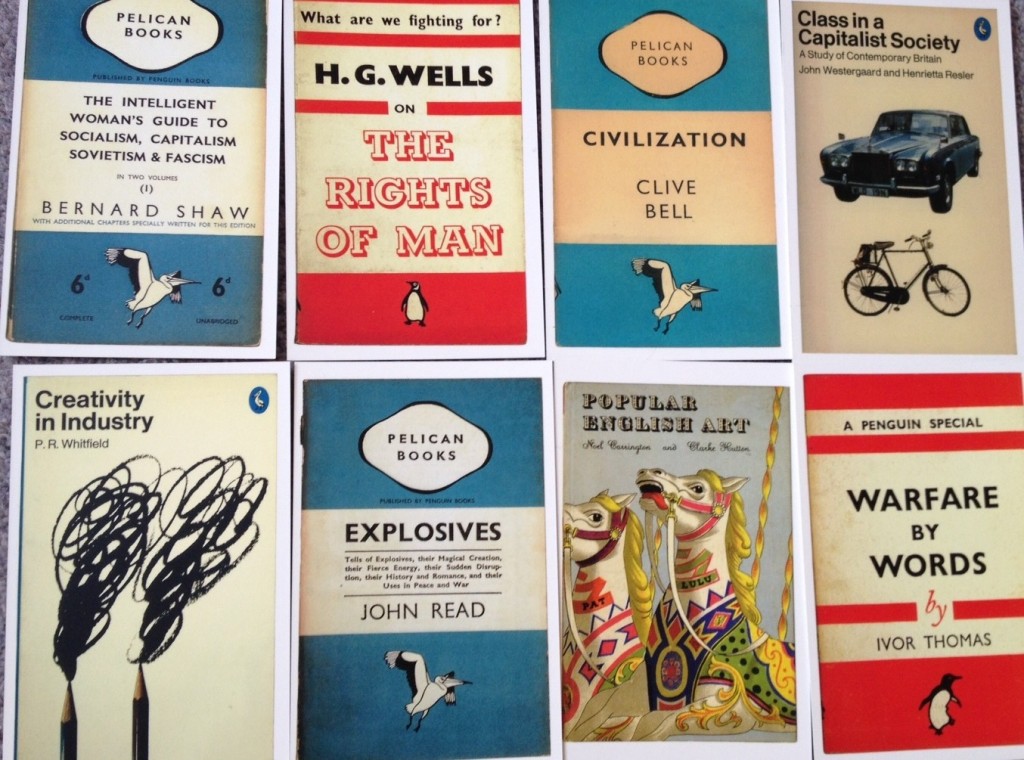

Which takes me onto the third link, this post by Toby Mundy criticising Amazon’s philistinism in selling books at ever lower prices by squeezing publisher’s margins. He frames it in terms of the contribution of the book form – long, complex, detailed – to the human achievement of civilisation – but finally makes it an argument about short term consumer gains versus the long term: “The result of these changes will be a much diminished eco-system for stories and ideas, with many fewer publishers and authors earning anything. Ultimately this may benefit a small number of people who hold stock in Amazon, but it will do precious little for our wider culture.”

The common theme is the value of culture, of course, in its form as a photo or book say, and how that value is distributed. It is about monetary versus non-monetary value, and about power in the marketplace and the polity. The specifics are new, the debate is old. All property involves social conventions derived from power relationships. When I sit in a cafe to have a cappucino, I have purchased the liquid in the cup, but not the cup – the owner would be outraged if I walked off putting the cup in my bag. That’s the convention, and the price for the drink reflects competition among local cafes.

I think the mistake many people make in thinking about who gets the value from digital cultural products is to assume that the market from which content creators (or publishers) will get their dibs are the same as in the offline world. The technological ease of copying (cf Walter Benjamin, [amazon_link id=”0141036192″ target=”_blank” ]The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction[/amazon_link]!) means the conventions have to change, and changing social conventions is never a smooth process. But George Gissing was poor long before the Web, despite being a marvellous writer, and I’m willing to bet David Slater will be a better-known and potentially more prosperous photographer post-ape selfie incident.

[amazon_image id=”0141036192″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (Penguin Great Ideas)[/amazon_image]