Having been guiltily reading a thriller or two, as well as David Olusoga’s Black and British, this is a brief post about an economics paper I’ve read, Paul David on Zvi Griliches and the Economics of Technology Diffusion. (Zvi was one of my econometrics teachers at Harvard, a very nice man who was still so obviously brilliant that he was a bit scary. He would ask a question which might be completely straightforward but one would have to scrutinise it carefully before answering, just in case.) Anyway, the Paul David paper is a terrific synopsis of three areas of work which are implicitly linked: how technologies diffuse in use; lags in investment, as new technologies are embodied in capital equipment or production processes; and multifactor productivity growth.

As David writes here: “The political economy of growth policy has promoted excessive attention to innovation as a determinant of technological change and productivity growth, to the neglect of attention to the role of conditions affecting access to knowledge of innovations and their actual introduction into use. The theoretical framework of aggregate production function analysis, whether in its early formulation or in the more recent genre of endogenous growth models, has simply reinforced that tendency.” He of course has been digging away at the introduction into use of technologies since before his brilliant 1989 ‘The Dynamo and the Computer‘. Another important point he makes here is that there has been little attention paid to collecting the microdata that would permit deeper study of diffusion processes, not least because the incentives in academic economics do not reward the careful assembly of datasets.

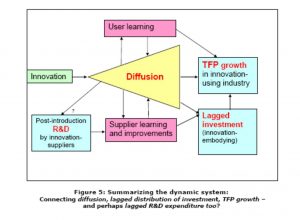

By coincidence, the paper concludes with a description of a virtuous circle in innovation whereby positive feedback to revenues and profits from a successful innovation lead to both learning about what customers value and further investment in R&D. Here is the diagram from the paper.

This was exactly the argument made yesterday at a Bank of England seminar I attended by Hal Varian (now chief economist at Google, known to all economics students as author of Microeconomic Analysis and Intermediate Microeconomics, and also with Carl Shapiro of Information Rules, still one of the best texts on digital economics). Varian argued there are three sources of positive feedback: demand side economies of scale (network effects), classic supply side economies of scale arising often from high fixed costs, and learning-by-doing. He wanted to make the case that there are no competition issues for Google, and so suggested that (a) search engines are not characterised by indirect network effects because search users don’t care how many advertisers are present; (b) fixed costs have vanished – even for Google-sized companies – because the cloud; (c) experience is a good thing, not a competitive barrier, and anyway becomes irrelevant when a technological jump causes an upset, as in Facebook toppling MySpace. I don’t think his audience shed its polite scepticism. Still, the learning-by-doing as a positive feedback mechanism argument is interesting.

This was exactly the argument made yesterday at a Bank of England seminar I attended by Hal Varian (now chief economist at Google, known to all economics students as author of Microeconomic Analysis and Intermediate Microeconomics, and also with Carl Shapiro of Information Rules, still one of the best texts on digital economics). Varian argued there are three sources of positive feedback: demand side economies of scale (network effects), classic supply side economies of scale arising often from high fixed costs, and learning-by-doing. He wanted to make the case that there are no competition issues for Google, and so suggested that (a) search engines are not characterised by indirect network effects because search users don’t care how many advertisers are present; (b) fixed costs have vanished – even for Google-sized companies – because the cloud; (c) experience is a good thing, not a competitive barrier, and anyway becomes irrelevant when a technological jump causes an upset, as in Facebook toppling MySpace. I don’t think his audience shed its polite scepticism. Still, the learning-by-doing as a positive feedback mechanism argument is interesting.