World War II literature isn’t my cup of tea normally, but there are some outstanding books. I loved Richard Overy’s [amazon_link id=”0140284540″ target=”_blank” ]Interrogations: Inside the Mind of the Nazi Elite[/amazon_link], about the period before the Nuremberg Trials when victors and prisoners had their first encounters about the cataclysm that had just ended. Overy’s powerful point is that people can switch between different moral universes astonishingly – scarily – quickly and thoroughly. Some of the prisoners had made that switch since their arrest. Another one of my favourite books is [amazon_link id=”0141042826″ target=”_blank” ]Most Secret War: British Scientific Intelligence 1939-45[/amazon_link] by R.V.Jones, about the huge espionage and intelligence effort, including the decoding of German communications by Bletchley Park – it covers the Whitehall and military hinterland as well, and the organisation of the enormous and wholly secret effort to deploy work at the frontiers of science and technology.

[amazon_image id=”0141042826″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]Most Secret War (Penguin World War II Collection)[/amazon_image]

[amazon_image id=”0140284540″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]Interrogations: Inside the Minds of the Nazi Elite[/amazon_image]

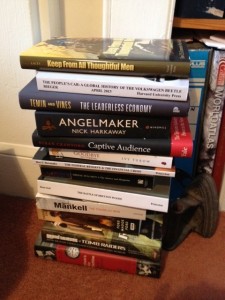

I’ve just started [amazon_link id=”1591144914″ target=”_blank” ]Keep From All Thoughtful Men: How US Economists Won World War II [/amazon_link]by Jim Lacey, and it already promises to join this distinguished company. Of course, it’s gratifying to see economists as heroes for once. Still, what I like about all these books is the reminder they bring that events are never, ever simple. Things turn out the way they do because of a lot of different contributory factors, few of them high profile. Or, as I like to put it in economist-speak, history is over-determined.

[amazon_image id=”1591144914″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]Keep From All Thoughtful Men[/amazon_image]