Laid low by a nasty cough all week, I’ve been paging through Benn Steil’s [amazon_link id=”0691149097″ target=”_blank” ]The Battle of Bretton Woods: John Maynard Keynes, Harry Dexter White and the Making of a New World Order.[/amazon_link] It’s a surprisingly gripping story, pitting the Americans against the British, and the Russians against the Americans. The Communist sympathies of White are fairly well known by now. Although this IMF Working Paper of 2000 (pdf) asserts that there’s some room for doubt, despite the confirmation provided by the [amazon_link id=”0140284877″ target=”_blank” ]Mitrokhin Archive[/amazon_link], by 2013 there is none. White was trying to further Soviet interests as he simultaneously – as this book shows – used the post-war financial architecture to crush any hope of a revival of British economic and geo-political power.

[amazon_image id=”0691149097″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]The Battle of Bretton Woods: John Maynard Keynes, Harry Dexter White, and the Making of a New World Order[/amazon_image]

The book quotes a 1947 Economist editorial: “Not many people in this country believe the Communist thesis that it is the deliberate and conscious aim of American policy to ruin Britain and everything that Britain stands for in the world, but the evidence can certainly be read that way.” The new dollar-centric financial structures were, Steil shows convincingly, intended to force Britain to keep holding out the begging bowl for international loans. He writes: “The US used its control of the IMF to deny Britain the dollars it needed to counter a run on sterling and blocked its efforts to secure emergency oil supplies.” But where De Gaulle had no hesitation in criticising the Americans, the British clung to the centrality of the ‘special relationship’ – indeed, as we still talk of this in the UK, it would have been surprising if it hadn’t had great force in the late 1940s.

The book ends by asking what the lessons of post-war monetary nationalism, embodied in the framework that survived until 1973, hold for today’s US-China imbalance. I think the counterfactual is just as interesting a question: what would the alternative history have been had Roosevelt not been so keen to weaken the old colonial power, and Harry Dexter White not so eagerly encouraged by his Soviet correspondents to accomplish this? If Keynes had survived longer, or if Britain’s industrial base had not been so thoroughly damaged by the conflict?

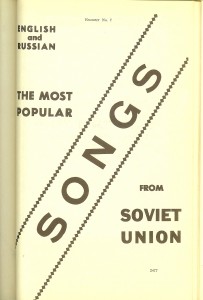

As for White, he almost became head of the IMF, but J Edgar Hoover – getting this one right – called him up before the House Un-American Activities Committee. White died of a heart attack soon after. I have a 1955 volume of the US Senate Judiciary Committee that reprints some of White’s papers, discovered at the summer home of the attorney general of New Hampshire – the volume is part of a study into ‘Interlocking subversion in government departments’. As the picture below suggests, the FBI’s suspicions of White was entirely understandable, even if it took some decades for KGB documents to confirm them.

How Harry Dexter White relaxed?

Here is the FT review of Benn Steil’s book.