“In the late 1950s and early 1960s, it was not necessary to emphasize that history was one of the principal sources of generalizations about the economy,” according to Robert Fogel (and his cast of co-authors) in [amazon_link id=”0226256618″ target=”_blank” ]Political Arithmetic: Simon Kuznets and the Empirical Tradition in Economics.[/amazon_link] That widespread understanding that economics is an historical science, like geology or maybe meteorology, was lost in the succeeding generations, and is only just returning – see, for example, the essays in [amazon_link id=”1907994041″ target=”_blank” ]What’s the Use of Economics[/amazon_link].

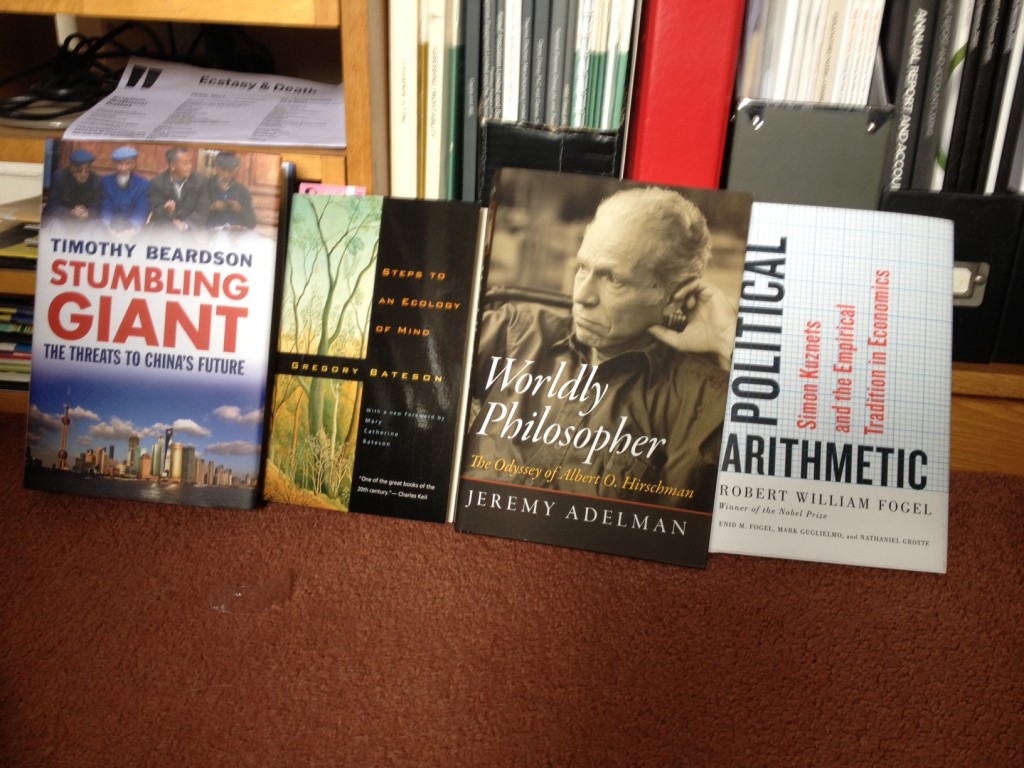

[amazon_image id=”0226256618″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]Political Arithmetic: Simon Kuznets and the Empirical Tradition in Economics (National Bureau of Economic Research Series on Long-Term Fac)[/amazon_image]

Political Arithmetic also emphasizes Kuznets’ insistence – as you might expect from one of the pioneers of national statistics – the importance of hands-on, detailed study of quantitative data for empirical economics. “High on his list of major dangers was the superficial acceptance of primary data without an adequate understanding of the circumstances under which the data were produced. Adequate understanding involved detailed historical knowledge of the changing institutions, conventions and practices that affected the production of the primary data.” Economists still frequently fall into the trap of not understanding the statistics they use, especially academic macroeconomists, who have fallen into the habit of downloading data from easily accessible online sources without giving any thought to how the statistics might have been collected. (Professional and applied micro-economists are typically more careful because less likely to be using the standard online databases.) Young economists are not even taught basic data-handling skills – such as the simplest precaution of printing out all your data series in straightforward charts to check for data-entry errors and outliers, before running the simplest regression or correlation.

These descriptions of Kuznets’ approach to economics certainly appeal to me, but overall I was disappointed by this book. My own book on the history of GDP is out later this year, and as Kuznets is such an important figure in national accounting, I was expecting to find all kinds of insights needing to be marked up on the proofs. However, Political Arithmetic turns out to be very short, more of an extended essay, so there are no details about Kuznets’ work on either national accounting or income and growth not to be found in previous books. At the same time, I think it fails in its claim to give an overview of Kuznets’ contribution to economics; there are elements of this in chapters on the way academic economics came to have a role in policy in the early 20th century, as well as on the emergence of national income accounting, but they don’t knit together in an effective synopsis. Maybe four co-authors are too many for a 118 page book.