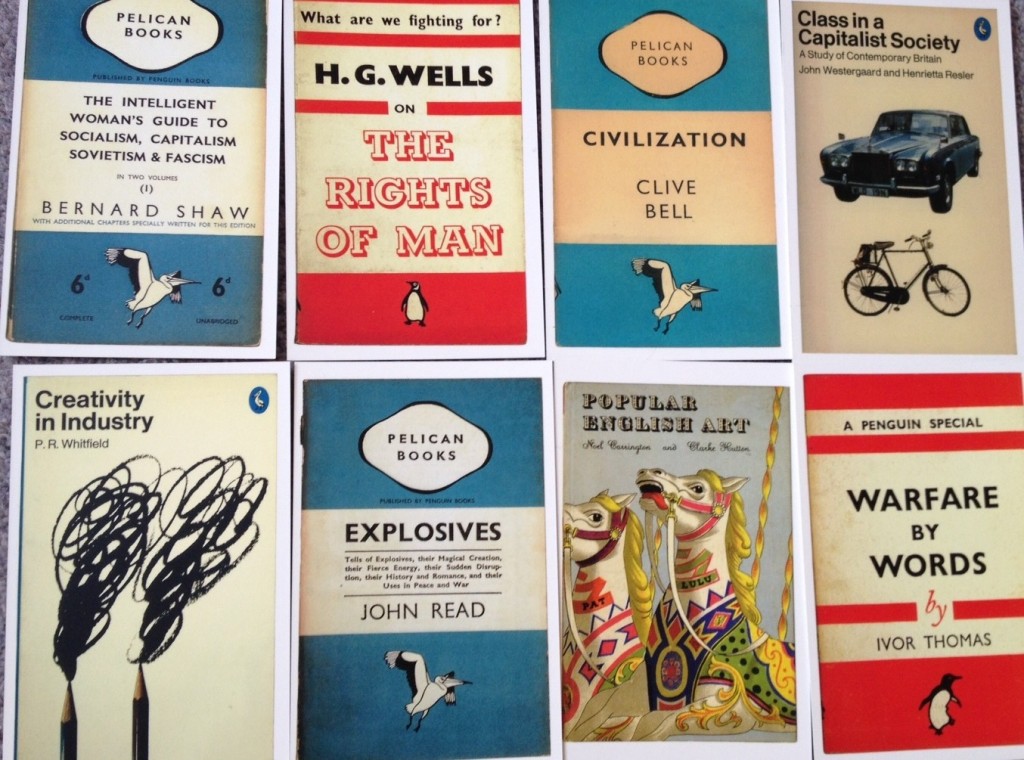

“He just wanted a decent book to read.” That’s the creation story of Penguin Books, as recounted on the inside of a box of postcards of Penguin/Pelican book covers I got for Christmas, ‘he’ being the founder Allen Lane.

The precedent of Penguin’s various series of non-fiction books – the Pelicans, the Specials, the ‘modern economics’ series – along with earlier examples such as the Left Book Club is what led me to wonder if I shouldn’t dabble in publishing some books I’d like to read myself. They would cover economics and technology. They would be short enough for a train journey – in 1935, Allen Lane was fruitlessly looking for something to read on Exeter Station. The authors would be authorities in their field but would write accessibly, and they would have something to say, something with public policy relevance. So the Perspectives series was born, in association with the London Publishing Partnership.

The first four titles are Jim O’Neill’s The BRIC Road to Growth; Bridget Rosewell’s Reinventing London; Andrew Sentance’s Rediscovering Growth After the Crisis; and Julia Unwin’s Why Fight Poverty. There was a soft launch just before Christmas, a separate launch for Bridget’s book last week, and tomorrow night an event on Andrew’s book.

[amazon_image id=”B00I124BKO” link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]The BRIC Road to Growth (Perspectives)[/amazon_image][amazon_image id=”B00I11G7FW” link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ][/amazon_image][amazon_image id=”B00HZ1YU4Y” link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]Rediscovering Growth: After the Crisis (Perspectives)[/amazon_image][amazon_image id=”B00I124BLS” link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]Why Fight Poverty? (Perspectives)[/amazon_image]

I’m biased, but I think these four live up to the aim of having a clear and authoritative message. Jim argues that the shift in the world’s economic centre of gravity is not in the future – it has already happened, and global institutions need to adapt swiftly. Bridget makes the case for London’s ability to reshape its economy beyond the financial sector, but needs to focus on services other than finance and have in place the right housing, infrastructure and external connections to enable growth. Andrew says that although the UK economy is starting to recover, the lean years are not over yet and we need to get used to a much slower pace of growth than we enjoyed before the crisis. Julia convincingly shows how negative emotions – fear and guilt – get in the way of a rational set of policies to tackle poverty.

Upcoming titles include Dave Birch on digital identity as money, David Walker on when public outsourcing to the private sector works, and when it doesn’t, and Kate Barker on how to get more housing built.

It has been an educational experience publishing books. Dealing with Amazon is tough if you’re small, but of course Kindle editions are essential. It’s a crowded market: there are lots of short, pithy books, lots of small presses and lots of self-published titles out there. But so far, so good. I’ll post occasional updates.

Forerunners