I’ve begun reading an intriguing book, [amazon_link id=”019979412X” target=”_blank” ]Knowledge and Co-ordination: A Liberal Interpretation[/amazon_link] by Daniel Klein. The author, someone I’ve not come across before, doesn’t go out of his way to be accessible, and also starts out describing his close identification with hardliners of the Austrian School. So I was preparing to take a look and write the book off as eccentric. But there’s proving to be enough of interest to have kept me going. For one thing, the author is a big fan of Deirdre McCloskey on [amazon_link id=”0299158144″ target=”_blank” ]The Rhetoric of Economics[/amazon_link], and of [amazon_link id=”0393329461″ target=”_blank” ]Thomas Schelling[/amazon_link] on game theory. I also liked this comment at the start of Chapter 2:

“Economists often talk of asymmetric information, but they rarely talk of asymmetric interpretation. They rarely talk of discovery, imagination or serendipity, and consequently they tend to neglect these as vital factors of economic progress. They often carry over their mental habits to public policy.” (p11)

And he goes on to quote Hayek:

“To use as a standard by which we measure the actual achievement of competition the hypothetical arrangements made by an omniscient dictator comes naturally to the economist whose analysis must proceed on the assumption that he knows all the facts which determine the order of the market.”

The challenge to economists who comment on public policy is a powerful one: is the assumption of omniscience, an objective external perspective, on our own part – rather than the assumption of rationality – our real failing?

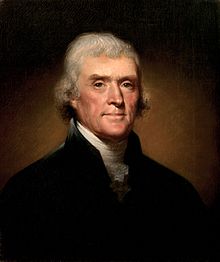

[amazon_image id=”019979412X” link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]Knowledge and Coordination: A Liberal Interpretation[/amazon_image]