I’ve been mulling over the Malcolm Gladwell comment mentioned in my previous post – “Poverty is not deprivation; it is isolation.”

Much of my consultancy work during the past eight years has concerned the social and economic impact of mobile phones in low-income countries. The first report I did for Vodafone (on the impact of mobiles in Africa, in 2005, Paper 2 in this series) included a now-famous piece of econometrics by Len Waverman and co-authors estimating that an additional 10 mobile phones per 100 people (from 1995 to 2003) had raised a country’s per capita GDP growth 0.6%. Although this was large, an estimate we thought was probably biased upward a bit by simultaneity despite the team’s best efforts to take this into account, it made sense that the impact could be large when looking at earlier research on the effects of fixed line telephony in the US.

One comparison Len made always stuck in my mind: at that time mobile penetration rates in a country like Kenya were similar to fixed-line penetration rates in a country like France in the early 1970s. When I grew up in northern England in the 1960s and 70s, few of us had phones at home – we had to walk about 10 minutes to the nearest call box. My parents got a phone in the late 1970s, and shared the line with another house even then. Within the past generation, communication has changed the way all of us on Earth engage in everyday economic (and social) activities like shopping or finding work.

[amazon_image id=”B004SHO570″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]Linked: The New Science Of Networks Science Of Networks[/amazon_image]

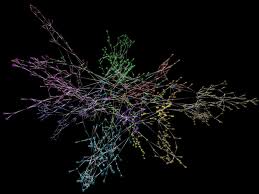

I looked back at the first book I read about networks, Albert-Lásló Barabási’s [amazon_link id=”B004SHO570″ target=”_blank” ]Linked: The New Science of Networks[/amazon_link]. He points out that the structure of the economy or its sub-components like industries or firms is a tree. Poor countries, or people are at the outmost branches, with the fewest opportunities. Unhealthy, uncompetitive industries have too few over-large trees whose shade destroys the vigorous undergrowth.

Andy Haldane at the Bank of England has spoken of the need to apply network thinking to the banking industry, and the risk of systemic failure. Mainstream economists actually need to consider much more carefully how network models might apply across the board, as a few pioneers such as [amazon_link id=”0415594243″ target=”_blank” ]Alan Kirman[/amazon_link] and [amazon_link id=”0571197264″ target=”_blank” ]Paul Ormerod[/amazon_link] have long argued.

Thinking about networks is natural in the field of telecoms, but the connection between the physical networks that fundamentally underpin the economy and the mental models we use to analyse the economy hasn’t been fully made. The economy has been rewired since around 1980 but economics hasn’t yet.

The internet tree