It seems a bold mission, to propose a solution to the Euro crisis in 80 pages. All the more so when the authors of The Euro in Danger: Reform and Reset, Jagjit Chadha, Michael Dempster and Derry Pickford, compare the present situation in Euroland with Lord Palmerston’s verdict on another European crisis: “Only three people…have ever really understood the Schleswig-Holstein business – the Prince Consort, who is dead; a German professor, who has gone mad; and I, who have forgotten all about it.”

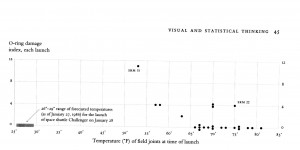

This short book or long pamphlet also acknowledges that, as in the old joke, if you wanted to get to a sustainable Eurozone currency union, you wouldn’t be starting from here. It has some extraordinary charts, including one recording the movement of Target 2 balances, another showing the movement of unit labour costs – the message of every one of them is a story of dramatic divergence between the core and the periphery since 2009.

Nevertheless, the authors argue that the Euro should be saved, and they have some proposals for doing so. Their suggestion is what they describe as the ‘reset’ option: the peripheral countries should be allowed out temporarily in order to return as members when certain conditions, including those elusive structural reforms in labour markets, had been met.

Meanwhile, the book argues, the monetary union of the core Euro states should be strengthened, with steps towards full banking union and the ECB to act as a classic lender of last resort in future crises, an independent fiscal monitoring body, and a European Sovereign Bankruptcy Court. The authors would also ban certain derivatives transactions including the ‘Tobashi swaps’ used to hide the scale of Greek and Italian sovereign debt (widely sold, the book reports, by Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, JP Morgan Chase, Deutsche Bank, Bank of America, Merrill Lynch, Nomura…..).

As for the ‘reset’ option, this would require temporary departure for the Eurozone and devaluation before joining a crawling peg against the Euro, a haircut on sovereign debt, monitoring of fiscal policy by an independent body, and increased reserve and capital requirements for domestic banks, as well as economic reform.

Reading about such details always makes me feel about as well-informed about the Euro crisis as I am about Schleswig-Holstein. The one thing that’s perfectly clear to me is that the peripheral countries will need to default in some form, as their debt burdens are unsustainable. Others who are more expert than I am will be better placed to evaluate the specific proposals in this book. It does all seem entirely level-headed, but one has to wonder about the political feasibility of sensible reforms.