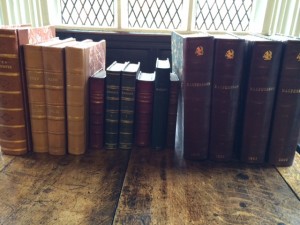

Yesterday I was in the magnificent Chetham’s Library in Manchester with Colm O’Regan, recording a radio programme featuring the desk at which Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels studied for 6 weeks in the summer of 1845. The librarian Michael Powell set out for us the yard of books the two had read during that visit, saying they were very dull including for example William Petty’s [amazon_link id=”B00A1G5MHY” target=”_blank” ]Essays in Political Arithmetick[/amazon_link].

A yard of reading by Marx and Engels

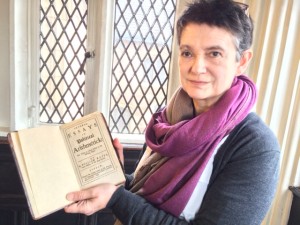

Well, be still my beating heart! As the author of a brief (but affectionate) history of [amazon_link id=”0691169853″ target=”_blank” ]GDP,[/amazon_link] I was delighted to find it had been one of Marx’s early economics texts. Here I am holding the very copy that K.M. read (no marginalia, unfortunately). Rooting around on Google Scholar this morning, I find that Marx emphatically considered Petty to be the founding father of political economy, in [amazon_link id=”1840226994″ target=”_blank” ]Capital[/amazon_link] citing Petty’s description of capital as ‘past labour’. (Bizarrely, Google said it had witheld some search results because of data protection law – ??)

Me holding Petty

Here is Colm, metaphorically scratching his head about one of the other books, a super-dull history of trade since ancient times, in three volumes. More information about our podcasting project in the weeks ahead.

Colm O’Regan dipping into the history of trade

Marxian economics is a chasm in my education, although I did try to read Capital when young.[amazon_link id=”0140445684″ target=”_blank” ]Capital: Critique of Political Economy v. 1 (Classics S.)[/amazon_link] The [amazon_link id=”0141397985″ target=”_blank” ]Communist Manifesto[/amazon_link] is good and stirring stuff of course, and sitting in the Chetham’s Library, which could have served in a Harry Potter film, you understand why they had spectres in mind. However, for me Engels’ book, [amazon_link id=”0199555885″ target=”_blank” ]The Condition of the Working Class in England[/amazon_link], is one of the finest pieces of analytical economic reportage, and a true call to arms.

[amazon_image id=”0199555885″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]The Condition of the Working Class in England (Oxford World’s Classics)[/amazon_image]

Update: the entire list of books read that summer by Marx and Engels, kindly provided by the librarian Michael Powell, is:

Aikin, John Description of the country from thirty to forty miles around Manchester (London, 1795)

D’Avenant, Charles Essays on peace at home and abroad (London, 1794)Discourses on the publick revenues and on the trade of England (London, 1698)

Eden, Frederick Morten The state of the poor, 3 vols. (London, 1795)

Gisbourne, Thomas Inquiry into the duties of men in the higher ranks and middle classes of society in Great Britain (London, 1795)

Macpherson, David Annals of commerce, manufactures, fisheries and navigation, 4 vols. (London, 1805)

McCulloch, John Ramsay The literature of political economy (London, 1845)

Petty, William Essays in political arithmetick (London, 1699)