Diego Comin, Mikhail Dmitriev, Esteban Rossi-Hansberg have written a fascinating summary of their work on the diffusion of technology, published as a CEPR working paper. The headline is that distance matters, and that the diffusion process follows the same kind of pattern seen in the transmission of epidemics.

The authors note that their data (covering a large number of technologies) strongly confirms the pattern of east-to-west diffusion of technology described by Jared Diamond in his fantastic book [amazon_link id=”0099302780″ target=”_blank” ]Guns, Germs and Steel[/amazon_link]. The argument there was that geographical latitude explained the success of certain important agricultural innovations. So how could it also matter for the spread of, say, ATMs, cellphones or TVs? “Distance is a significantly more important impediment across parallels than across meridians.” The VoxEU authors suggest this is because technologies are spread – like diseases – by people, and the patterns of social contact for reasons of history and geography are more prevalent east-to-west than north-to-south.

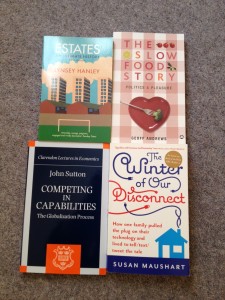

[amazon_image id=”0099302780″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]Guns, Germs and Steel: A short history of everybody for the last 13,000 years[/amazon_image]

There is a forward-looking aspect to this, of course. Trends in the movement of people do change over time, and have changed with globalisation. More significant, anybody thinking about long-term growth needs to think about the adoption of ideas. Most new ideas will come from outside the borders of one country, attached to people from elsewhere. One cannot think about innovation (among other things) without thinking about immigration – as Ian Goldin, Geoffrey Cameron and Meera Balarajan argued in their book [amazon_link id=”069115631X” target=”_blank” ]Exceptional People: How Migration Shaped Our World and Will Define Our Future[/amazon_link].

[amazon_image id=”069115631X” link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]Exceptional People: How Migration Shaped Our World and Will Define Our Future[/amazon_image]