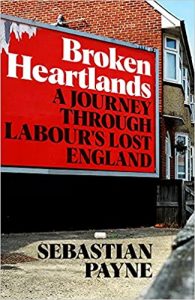

This is a meetings-free week, taking advantage of the fact that people are largely willing to take no for an answer until mid-Jan, and I’ve also still got (I hope) quite a fierce email autoreply telling people to go away. It’s amazing how much more work this makes possible, even leaving time to catch up on reading. The latest book, which I started when it came out but has since been parked on the side table, is Sebastian Payne’s Broken Heartlands: A Journey Through Labour’s Lost England.

I really enjoyed this. It’s classic, careful yet evocative reportage from ‘Red Wall’ seats across the northern part of England. It starts in Gateshead, the author’s home territory, and, via a number of these once solidly Labour and now – extraordinarily – Conservative constituencies, ends up in Burnley, close to mine. It’s a very fair book: Payne lets people talk, reports what they said at decent length, and limits his own opinions to comments on prospects for the various parties in elections that lie ahead. (There’s a bit more discussion of electoral arithmetic than I wanted but that’s a quibble.)

One key message I took is not to over-generalise. There is indeed a lot of poverty in the Red Wall seats but also a lot of affluence, in the places where old heavy industry has been successfully replaced, so part of the story is the growth in numbers of ‘natural’ Conservative voters around the country. The truer generalisation is the substantial decline of public amenities around the English regions – transport, libraries, pleasant high streets. Another message – and in fact one on which the book quotes me (and many others) – is the crying need for devolution of powers within England.

A few other things struck me. One – a parenthesis in the Sedgefield chapter – was this: “nearly all the Red Wall seats had a train station closed in the infamous [Beeching] programme.” Reminded me of this marvellous paper on the Beeching cuts by Steve Gibbons. What economic, social and cultural vandalism Dr Beeching unleashed with the massive scope of his cuts: a great lesson in the imperative of taking into account network effects and spillovers in a cost-benefit framework, and the fact that some subsidies are worth every penny.

Another section was a discussion with Neil Kinnock, in which the former Labour leader observed that what has been lost is not so much collective sentiment in former industrial areas as the security that came with the social fabric of the post-war era. Kinnock said that modern individualism “is a source of choice but it’s also a source of weakness and insecurity. You’re on your own. In previous decades the one thing you weren’t, in richness and then poverty, was on your own.” I read this as Keir Starmer made security the theme of his New Year speech so presumably this will be part of Labour’s pitch for 2024.

Above all, though, Broken Heartlands is a terrific read and gives a real flavour of its territory. I’m just glad it wasn’t me out on the road in the North in the cold, wet winter of a pandemic.