This week I’ve been travelling – two days in Newcastle and lots of meetings. It included a visit to the set of The Paradise, the BBC drama based on Zola’s [amazon_link id=”2218745208″ target=”_blank” ]Au Bonheur des Dames[/amazon_link]. It’s one of the novels I haven’t read, despite being a huge Zola fan. (Does any other British reader of this blog remember the superb, terrifying BBC dramatisation of Therese Raquin with Alan Rickman in the 1980?) So of course I’ll have to get the book now.

[amazon_image id=”0199675961″ link=”true” target=”_blank” size=”medium” ]The Ladies’ Paradise (BBC tie-in) (Oxford World’s Classics)[/amazon_image]

Meanwhile I bought Jeremy Bowen’s [amazon_link id=”0857208861″ target=”_blank” ]The Arab Uprisings[/amazon_link] at the station bookstore, just in case I ended up with some unexpected free time and no book (hah!).

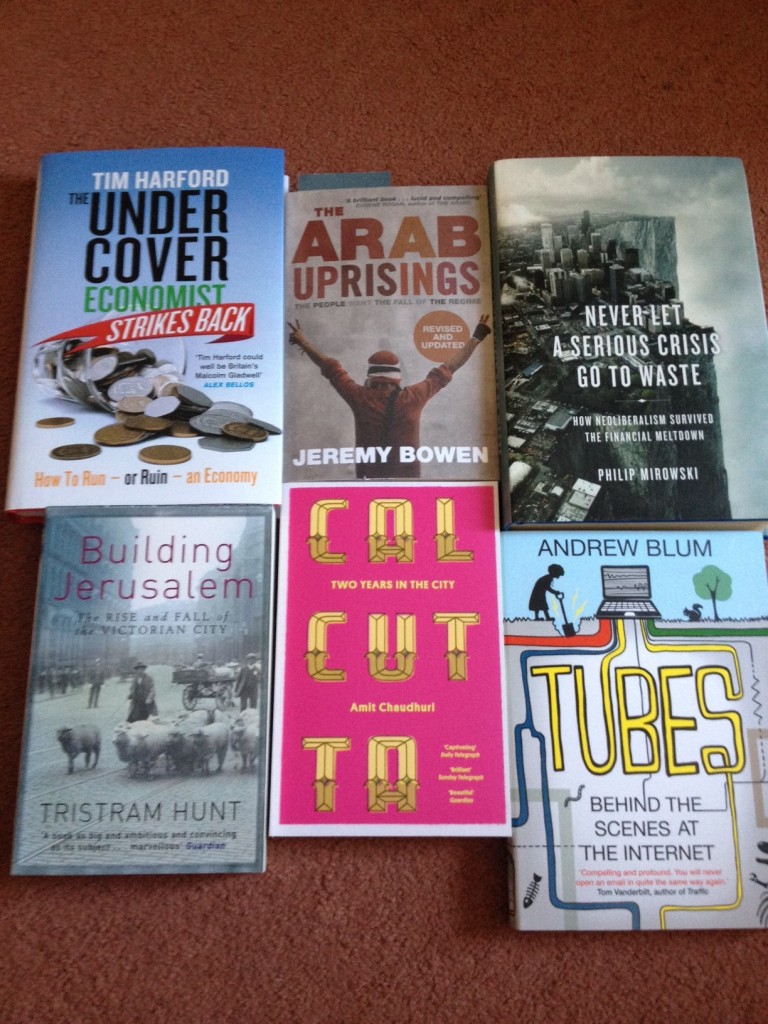

Then got home to my recent orders and a couple of incoming review copies. Here are the recent acquisitions. Good thing summer is coming up.

Recent acquisitions

Of course, this kind of appetite for more books (and I’m with Umberto Eco that it isn’t necessary to read all the books in one’s library/anti-library) lends support to the assumption of non-satiation in consumer choice theory. More is always better. The theory refers to more of the same and one could argue that each book title should count as a separate good, in which case non-satiation would not be a valid assumption (although a couple of my colleagues like to have the same book in physical copy and on an e-reader).

But that doesn’t mean Barry Schwarz’s [amazon_link id=”0060005696″ target=”_blank” ]Paradox of Choice[/amazon_link] is valid either. His examples include types of jeans or brands of cereal and toothpaste. But not only do I not want Prof Schwarz determining what kinds of jeans I’m allowed to wear, I never hear proponents of the paradox of choice arguing that there are ‘too many’ book titles, or charities to which to donate, or types of wine. Are we to suppose that the professional classes are less likely than the lower orders to be daunted psychologically by too much variety?

I’m planning to do a tiny self-experiment. Since two months I have a Kindle and I want to analyze what I’ve collected on it and why. And I want to test some hypotheses. I’m looking for applicable theories (I’m not an economist) and the two you mention above sound very relevant. I’m going to look them up.

I myself had thought about:

– classic supply curve – if something is cheap you will buy more of it

– decision costs – selection costs – even if a book is cheap or free the time to decide costs money (but I can’t find the right name and definition anymore)

– attention economy and branding as shortcuts for selection

Do you have more theories and models that I could apply?

Maybe the power of social norms in shaping your preferences. Are your choices affected by friends, or by being told in a review that a book is the hot new read?

Ah, found it! I meant: Search cost.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Search_cost

The problem with the paradox of choice is simply that not all product groups – which themselves must differ by individual – can be assigned to a universal decision making process such as that found in bog-standard microeconomic theory. (Or, on the off chance that there are any associate professors reading, there is heterogeneity among both consumers and goods, and incomplete information.)

Prof. Schwarz may think that a pair of jeans is a pair of jeans is a pair of jeans; I confess I am overcome with a similar sentiment on the toothpaste aisle. (Only if I cannot find Colgate Advanced Whitening, mind.)

For me, it’s another case of Economics in search of a universal theory where one should not exist. It should push the reader to embrace a problem-solution approach — the kind of approach which appears to be creeping into more and more macroeconomics since 2009.

Maybe one day in the distant future when cognitive science and neuroscience are further advanced, we can get to a universal choice theory. Meanwhile, I’m with you. Do you think macroeconomics is creeping in that direction? I wish it would creep faster.