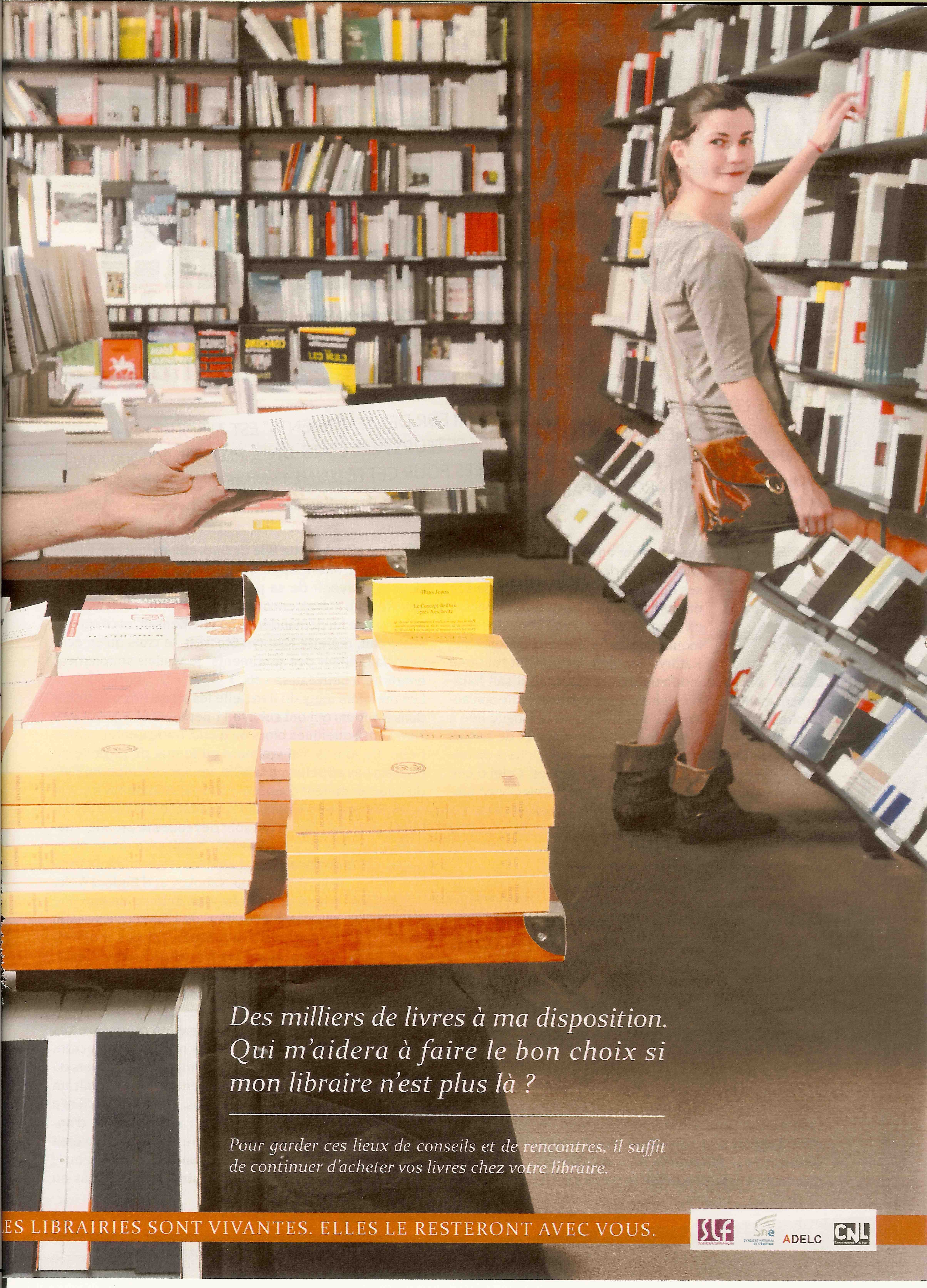

On holiday in France last week, I spotted an advert in Madame Figaro encouraging readers to continue to shop at their local bookstore. “With millions of books to choose from, who will help me decide if my bookshop is no longer there?” runs the copy.

Evidently, online sales are endangering bricks and mortar bookshops there too. What’s interesting about this familiar tale of decline – Borders in the US, Waterstones struggling in the UK – is that it’s always portrayed as the result of changing consumer habits. However, publishers play a part too. They choose how big a discount from the cover price of a book to give to different retail outlets. A combination of the market power of the biggest retailers – Amazon, some supermarkets – and the lower cost of distribution to their centralised warehouses means that publishers have always given bigger discounts to these outlets. The obvious consequence is that small bookstores can’t match the prices offered by their big competitors. As a particular title is the same everywhere, it’s no wonder consumers have changed their habits. If physical bookstores matter to publishers in the long term, as all publishers tend to claim, the publishing industry will need to change its habits too.

Meanwhile, here is the lovely bookshop in Toulouse which benefited from a few of my euros.

The Ombres Blanches bookstore in Toulouse

This captures my frustration with the book trade in the digital era. The obvious economic pressures from online produced EXACTLY THE SAME BEHAVIOUR from all actors in the trade and, consequently, a race to the bottom based purely on price and the inevitable elimination of all the weaker players. I know it’s hard to innovate in an old business when your margins are being shredded by newcomers on lower cost bases but some genuine innovation from the trade – developing exclusive product (playing Apple and Amazon’s game), investing in a really special customer experience, adding premium or experiential layers to the product mix etc. etc. – might have offered some differentiation from digital. Walking around a book shop (even a really good one) is essentially EXACTLY THE SAME EXPERIENCE as it was fifteen years ago. And the whole trade, top to bottom, still feels doomed.

One reason for the absence of innovation in all of these examples has also been insufficient competition and high barriers to entry in the business. However, I think bookshops would argue that *they* have tried to innovate – cafes, sofas, readings, 3 for 2 offers etc. And for me the bookshop experience has improved, and differs greatly between shops, mainly depending on the editorial intelligence behind the selection of range of titles and the display.

I’d contend that all the innovations you mention are essentially pre-digital. I can trace my first wide-eyed ‘sitting on a sofa with a cappuccino in a bookshop’ experience to a Barnes & Noble in NYC in 1994, some months before Bezos set off on his famous roadtrip! I know European bookshops have taken a bit longer to catch up but where is the POST-DIGITAL innovation? (as distinct from the post-Kindle innovation, which is pouring in now – now that IT’S TOO LATE!). I don’t want to sound impatient (I’m a book nut!) but really, so much energy has been committed to closing out the competition and to defending historic models. It’s heartbreaking.

I do strongly agree with your last point.

Much as I love bookshops, especially small independent ones, I’m a whole-hearted believer that more people reading more books is a good thing. I don’t have data, but I’m willing to bet that more books being sold is a good indicator of more people reading more books. Unless there’s evidence that publisher behaviour is leading to _fewer_ books being sold (either at higher margins*, or because the entire industry don’t know how to run a business), you’d have to say that their behaviour is ultimately for the good, even if it means fewer bookstores. (Unless you disagree with my first premise and would prefer fewer people read fewer books.)

* I think you could argue that, in the 21st century, barriers to entry to becoming a publisher are vanishing, so the “fewer books at higher margins” seems unlikely.

I’d agree wholeheartedly if not for a question about the range of books that get published and succeed in finding large numbers of buyers. In other words, are we moving to a small number of block busters and a long tail of commercially unsuccessful titles that aren’t widely read – and does that matter?